Zero to One Is a Subtraction Problem

My co-founder Ludo and I have worked together quite a bit over the years. One would think we know each other’s styles pretty well at this point. What surprised us in building SuperMe is our approaches to zero to one are quite different. Building SuperMe made something obvious: zero to one isn’t just about speed. It’s about surface area and conviction.

Operating Styles Are Context Specific

Ludo and I first got exposed to each of our styles when scaling Pinterest. Initially on different teams, I got to see Ludo’s creative problem solving and intuition for when to hack and when to scale engineering systems, and I think Ludo got to see my ability to strategically prioritize and frame problems to the rest of the organization that made what we were doing more legible to them.

We started working together again when Ludo brought me in to advise Whatnot. That exposed both of us to different aspects of our management styles, both because it was a different set of circumstances compared to Pinterest and because we had both gained a lot of new reps and skills from recent experiences at Lyft and Eventbrite. Ludo was operating at more scale, and given my part-time status as an advisor, I was more direct and less patient, trying to be as efficient with the smaller amount of time I had to help the company.

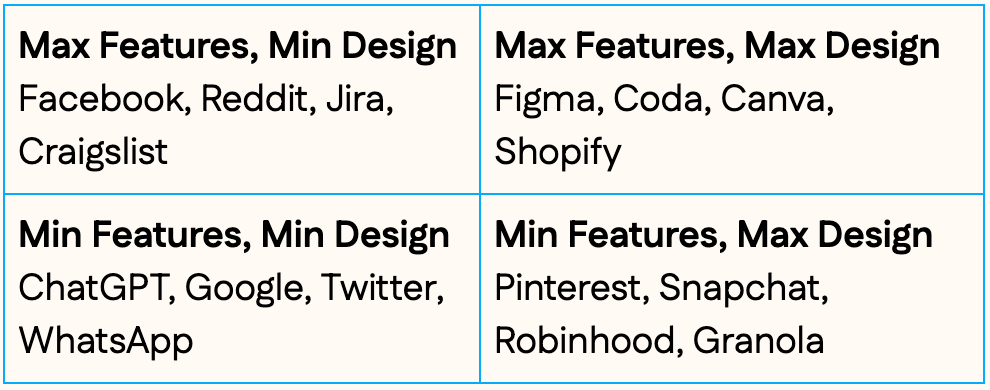

The Founder Surface Area Matrix

Working with Ludo zero to one as a co-founder has also been different. While both Pinterest and Whatnot were scaling experiences for companies that had product/market fit, we started SuperMe from scratch. Over time, we noticed two key axes on which we operate materially differently. Founders make two early bets going zero to one:

How much surface area to build?

How much aesthetic/brand polish to invest in?

Here’s my take on what quadrants famous companies started in:

Max Features, Min Design: Facebook, Reddit, Jira, Craigslist

Max Features, Max Design: Figma, Coda, Canva, Shopify

Min Features, Min Design: ChatGPT, Google, Twitter, WhatsApp

Min Features, Max Design: Pinterest, Snapchat, Robinhood, Granola

Many great companies move quadrants over time, and neither of these approaches are default right or wrong, and founders do not need to be aligned to the same bucket to be successful together, but each has pros and cons and optimal working model.

Maximal features → faster learning, harder to prune

Minimum features → easier to prune, but slower learning

Maximal design → stronger positioning, but slower learning

Minimal design → faster learning, weaker positioning

The surface area decision determines your pruning burden. The more you build, the more you must cut. The more polished your product, the harder those cuts feel.

Distractions vs. Compounding Value

For a consumer network, as mentioned in my last essay, there are three variables: value prop, target audience, and network density, and this impacts how you act in the different modes above.

In a maximal feature model, any experiment that works needs to enable a new step in the process that clears the table of other experiments to triple down on what is working. The Instagram founders famously did this with photo filters of their original social app Brbn, as did Pinterest with saving from their original shopping app Tote.

It’s hard to give up on other experiments when you’re a feature maximalist. Some of those other experiments could also be hits with more investment or more time. Sunsetting them is brutal for builders and initial users.

To triple down on hits, you need a clear process for handling misses. The key question is always is this feature a distraction or something that compounds with higher density? In networks, the line between distraction and compounder is blurry because value increases with density.

You can’t triple down on hits if you can’t diagnose what’s wrong with your misses. If you keep pouring energy into misses, you starve your hits.

One useful process is a formal experiment review after a feature has been live for a while that answers:

Is it a hit? If so, what are we removing from our feature set and future roadmap to focus on it?

If it’s not a hit, is it a distraction that should be killed or is there evidence to suggest its value will compound?

If it’s a compounder, do we iterate now, let it sit, or intentionally defer it until density is higher?

Feature maximalists are more prone to distraction risk. Feature minimalists are more prone to missing latent compounders.

Understanding the Full Vision

Consumer products don’t win by chasing engagement alone. Because LTV is lower than in SaaS, consumer interest must convert into defensibility.

One exercise that we found helpful in answering the questions above is “is this feature required for the full vision?”. In order to answer this question, it helps to go back to some of the key questions Gilad and I proposed in our platform essay:

What does the company need to own?

What does the company want to compete to win?

What does the company want to attract?

What does the company want to reject?

If a feature is firmly in the first bullet for your long term success, it’s a compounder. Any other answer makes the feature a hit or a distraction. So, it’s either working and helping you grow and get closer to vision, or it needs to be killed.

–

Zero to one isn’t about building fast. It’s about pruning fast. You will try things that don’t work. The only question is whether you can recognize them, and whether you know what you’re protecting when you cut them. If you don’t know what you need to own, you won’t know what to remove.

Feel free to ask Casey AI more about this topic.

Currently listening to BOC Maxima by Boards of Canada.

Loved the clarity here. Perception of where one is in that quadrant tends to be the source of major misalignments that tend to take long to reconcile. Not just in founding teams, but in smaller organizational units too.